True or false: New research shows that for older people, a faster gait leads to a longer life.

True or false: New research shows that for older people, a faster gait leads to a longer life.

Answer: False — despite news coverage to the contrary (apparently).

Since this is a blog about curriculum-related matters, I want to start by explaining why this post is even here. Then I will review the story about gait and longevity, and after that I will expand on how this case of bad journalism can help shed light, I believe, on persistent problems in education theory, practice, and policy.

This post presents a case of reporting a relationship between measurement and the significance of measurement in a way that mistakes correlation for causation. This, of course, is a common and familiar form of error in dealing with statistical information, and is routinely dealt with in introductory courses on methodology, or in any kind of natural or social science.

I think this case is especially worth considering, however. For one thing, the problem with the misreporting here is particularly easy for anyone to understand, but not so immediately obvious that everyone would see it right away, without reflection. (At least, the editors did not see it, apparently.)

More important, for this blog: I think the misinterpretation here is suggestively analogous to the ways that the significance and practical implications of test scores are commonly misinterpreted in education, with ramifications for theory, practice, and education policy.

First, let’s note the headline of the WebMD story, and the first sub-section heading:

Walking Faster May Lead to a Longer Life

Faster Pace Boosts Life Span

The headline and subhead are both reporting in terms of causation, although the article in JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association) is careful to avoid such causal interpretations.

The more careful, and more justified, interpretations are suggested by the headline and subheads in the Wilmington News Journal, where I learned about the study, and in the USA Today article where Janice Lloyd’s story first appeared.

By Ronald A. Fontana, UPMC Medical Media

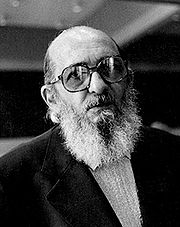

As USA Today puts it in the caption to their photograph (at left):

Edward Gerjuoy, 92, a professor emeritus of physics, walks at a pace of about 3 mph. Researchers say he has a 40% chance of living to 102.

In other words, Dr. Gerjuoy’s pace can be used as a predictor of possible longevity, or an indicator of the physical conditions that could contribute to his chances for a longer life-span; but his gait is not an independent causal variable that will “boost [his] life span.”

If he were to walk more slowly while maintaining his same health conditions, the statistical correlation does not say that he’d be expected to die earlier as a result. And he wouldn’t be expected to live longer by walking faster, except insofar as that might contribute to improvement of his underlying health conditions.

The proper interpretation is clearly articulated in this video from JAMA:

Gait speed is not a measure of longevity. It is not even a direct measure of the causes of longevity. It does measure something that correlates with causes of longevity; hence it can be used as a sort of proxy for more direct (but theoretically and practically more difficult) measures of the nebulous complex of factors that contribute to longevity.

I think this example by analogy could be used to help show the (less obvious?) fallacy of using test scores as if they directly measure such things as learning, knowing, and understanding.

A specific example: When I was in grade school, we got tested a lot. I went to grades 5-12 in Cedar Rapids, Iowa — about half an hour from Iowa City, home of the ACT testing enterprise — and we got the full battery of Iowa tests of basic skills, educational development, and whatever. When we got back our results in terms of percentile scores, we were always told that the Vocabulary score was the most significant, since it was the best indicator of general intelligence. (I think they did this so that students would not be overly concerned about their scores in Reading, Math, and other more specific areas; in my case, my percentile ranking on Vocabulary was always markedly lower than my other scores.)

I can certainly believe that vocabulary may be the best convenient, reliably measured indicator of literacy, or even of general intelligence (insofar as any such thing really exists).

But if so, that does not mean that drilling students in vocabulary is the best way (or even a particularly good way) of enhancing their literacy, or improving their intelligence.

It is reasonable to think that literacy develops with experience in reading, and that children with larger vocabularies will (as a statistical generality) tend to be those with more reading experience; such that within a tested population, variations in vocabulary would correlate with variations in literacy levels.

Attempts to improve literacy by drilling in vocabulary, instead of or without the reading experience that could otherwise enrich a child’s vocabulary, could boost vocabulary scores directly — in a way that would not reliably predict that literacy has been enhanced to the level that might be predictable if that same vocabulary had occurred as a by-product of reading experience.

In this way, the vocabulary drill could actually destroy the very relationship between reading and vocabulary that could otherwise provide a basis for using vocabulary scores as a proxy for literacy levels.

School programs, practices, and policies that aim directly at improvement of test scores, in this way, can undermine the relationship between test performance and the learning, knowing, and understanding that, as a result, can no longer be reliably assessed on the basis of test scores which have lost their validity as proxy measures.

I have seen such test-driven practices in my own area of social studies, as well as in math, science, and other subjects.

Just as faster walking could contribute to improved cardio-pulmonary and other conditions that contribute to longevity, drilling on vocabulary items could make some contribution to enhanced literacy.

Faster walking, in itself, is not the measure, nor the remedy — and much less the definition — of longevity. Just so, higher test scores are not themselves the measure, remedy, nor definition of intellectual achievement or ability.

References

Cesari, Matteo. “Role of Gait Speed in the Assessment of Older Patients” [Editorial]. Journal of the American Medical Association 305, no. 1 (2011, January 5): 93-94.

Studenski, Stephanie, and et al. “Gait Speed and Survival in Older Adults.” Journal of the American Medical Association 305, no. 1 (2011, January 5): 50-58.

You are free:

- to share – to copy, distribute and transmit this article, and/or

- to remix – to adapt this material; Under the following conditions:

-

- attribution – You must attribute this work in a manner that includes the information below (but not in any way that suggests that the author of this article endorses your use of this work).

Citation forms:

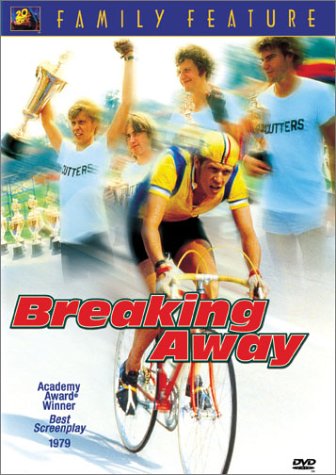

The specific sense in which Marx viewed capital as dead labor which, “vampire-like,” sucks the life from living labor, is amazingly (for a work in American popular culture) dramatized by one scene in the movie Breaking Away, written by Steve Tesich. The issue at hand is whether the young Dave Stohler (Dennis Christopher) will go to the University (and whether people like him — with his family and class background) belong in the university.

The specific sense in which Marx viewed capital as dead labor which, “vampire-like,” sucks the life from living labor, is amazingly (for a work in American popular culture) dramatized by one scene in the movie Breaking Away, written by Steve Tesich. The issue at hand is whether the young Dave Stohler (Dennis Christopher) will go to the University (and whether people like him — with his family and class background) belong in the university.